Money Market Funds, T-Bills, Large CDs, Small CDs: Americans Learn to Arbitrage

There’s no need to still pay a “loyalty tax” to the banks.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

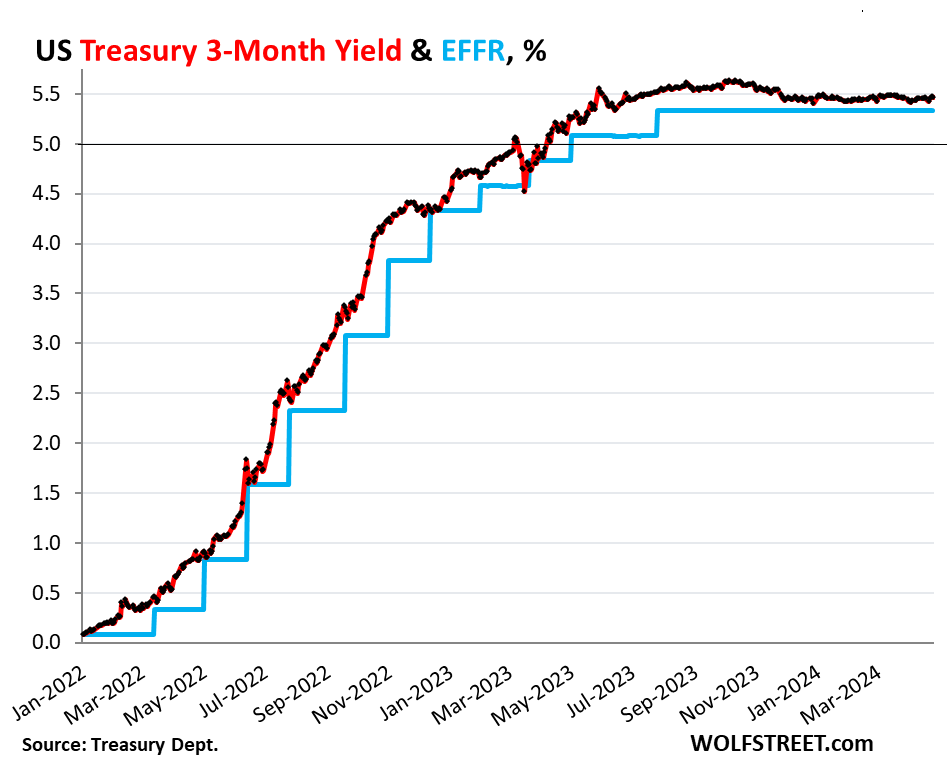

It’s sort of an anniversary: Treasury bills of three months or shorter have been selling at auction with yields over 5% since mid-April 2023. And since mid-May 2023, they have been selling with yields in the 5.2% to 5.6% range. Money market funds and CDs followed. These were finally reasonable returns, up from the ridiculous near-0% that had been in effect until January 2022.

Yields on low-risk short-term investments have come a long way since March 2022, when the Fed’s rate hikes started, and they have stayed over 5% for a year, and it looks like they’re going to stay there for longer, as Rate-Cut Mania has been obviated by resurging inflation.

The three-month Treasury yield closed at 5.48% on Friday. The effective federal funds rate (EFFR), which the Fed targets with its headline policy rate, has been at 5.33% since the last rate hike in July 2023. These used to be normal-ish yields two decades ago, and would have been considered low for many years before then, but here they are again. For a lot of investors, it’s the first time in their investing lives that they’re seeing those yields.

Those yields are not a gift from God, but a result of resurging inflation that has been eating into everything, and that finally belatedly forced the Fed’s hand.

Americans hate, hate, hate inflation. But they’re liking the 5%-plus yields on their cash, and put a lot of cash to work by yanking it out of their bank accounts and putting it in 5%-plus T-bills, money market funds, and “brokered CDs” that they bought through their brokerage accounts.

And that has forced banks to compete for deposits, to keep deposits from fleeing, and to attract new deposits to replace those that did flee, by offering attractive interest rates. And Americans have flocked to those CDs too, and they are switching back and forth, arbitraging rate differences, thereby keeping banks on their toes.

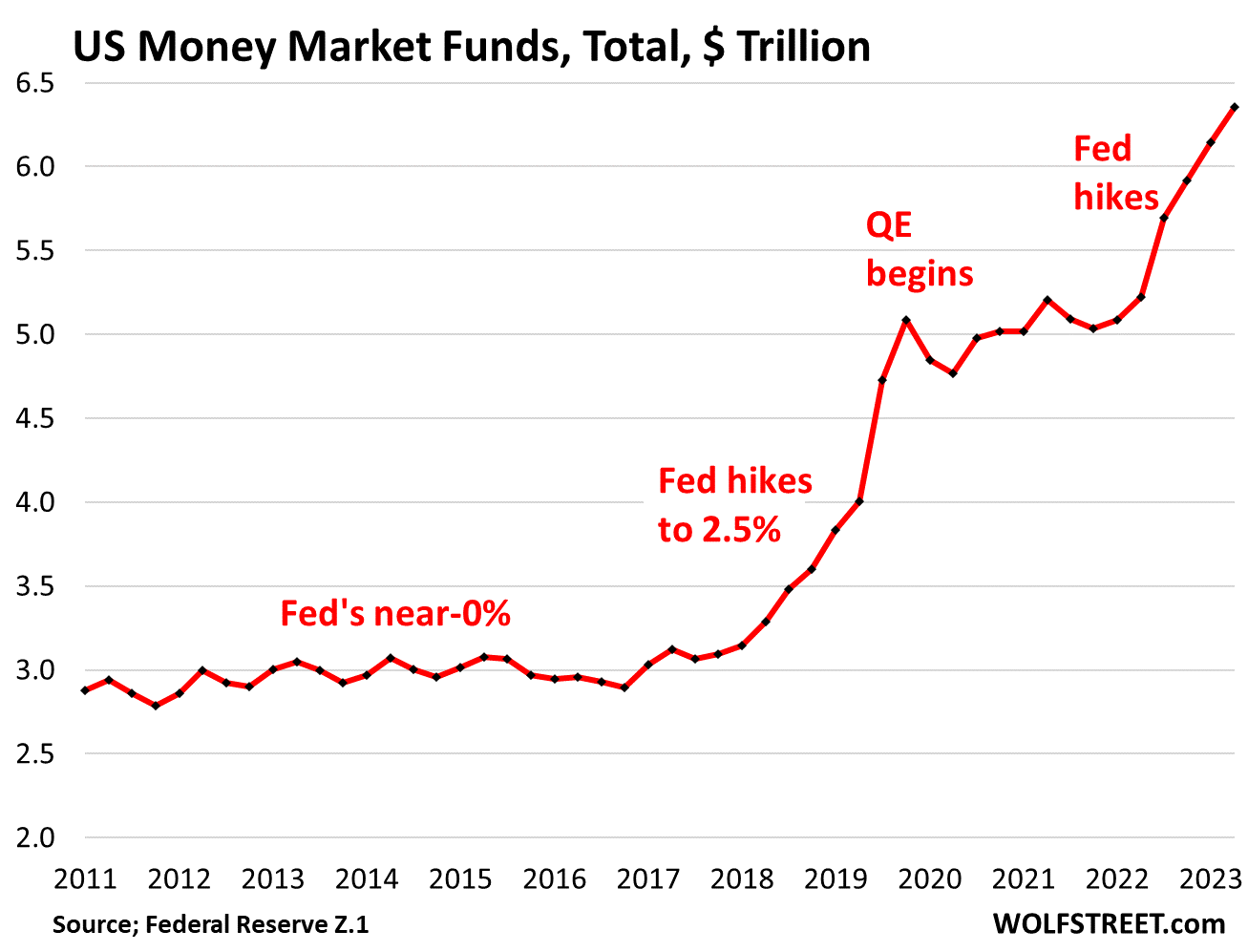

Money market funds (MMFs) that are tagged “retail” had swollen to $2.43 trillion as of April 3, but then there was a $300 billion dip around April 15 Tax Day when taxpayers withdrew cash to pay taxes. By April 24, the balance was down to $2.40 trillion, according to the weekly measure by ICI (Investment Company Institute).

This includes MMFs that invest in government instruments, such as T-bills; MMFs that invest in tax-exempt securities; and MMFs that invest in non-Treasury assets.

MMFs held by Households: A broader measure of MMF balances held by households, released by the Fed as part of its quarterly Z1 Financial Accounts, jumped to $3.6 trillion at the end of Q4, up from $2.6 trillion during the 0% pandemic era, and up from $1.6 trillion before the rate-hike cycle of 2017-2018.

Households are indirectly among the holders of institutional funds because the institutions include employers, trustees, and fiduciaries who buy those funds on behalf of their clients, employees, or owners.

MMFs are mutual funds that invest in relatively safe short-term securities, such as Treasury bills, repos in the repo market, repos with the Fed – what the Fed calls “Overnight Reverse Repos” (ON RRPs) – high-grade commercial paper, and high-grade asset-backed commercial paper, all of them with short maturities.

Total MMFs held by households and institutions spiked to $6.36 trillion by the end of Q4, according to the Fed’s data.

Banks have to compete with T-bills and MMFs.

Deposits are loans from customers to the banks and form the backbone of bank funding. When depositors yank their cash out, banks can collapse, and do collapse, see Silvergate Capital, Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and First Republic. When customers yank their money out because the bank’s interest rates on CDs or savings aren’t high enough, banks attempt to offer more attractive rates, but not across the board – that would be far too expensive – but to new money, and this initially happens with brokered CDs. That’s the first phase of banks reacting to T-bills and MMFs.

But as customers are starting to flee in larger numbers, it becomes imperative to retain the cash from existing customers by offering them competitive rates on cash they already have at the bank, and that’s the second phase, which started last year.

And so banks are offering CDs that yield 4% or 5% and more, even to their existing customers, and people have flocked to them. For banks, CDs (“time deposits”) provide funding that is more stable than savings or checking accounts whose cash can be yanked out instantly via electronic fund transfers.

Large Time-Deposits (CDs of $100,000 or more) surged by nearly $1 trillion since the Fed began its rate hikes, to $2.37 trillion by…

Read More: Money Market Funds, T-Bills, Large CDs, Small CDs: Americans Learn to Arbitrage